Even amongst investigational cancer drugs that ‘failed’ their trial, there are nearly always a small cohort of patients who did actually respond to the treatment, giving them months or years of their life back.

Yet, these drug are still often discarded, because the sponsor cannot figure out what factors drove response. Our models, which understands tumor biology far better than any human does, can discover these patients.

Given samples from a clinical trial, we can embed them alongside our thousands of other datapoints, allowing us to identify likely responders, subgroups within them, and how likely it is that each one would benefit.

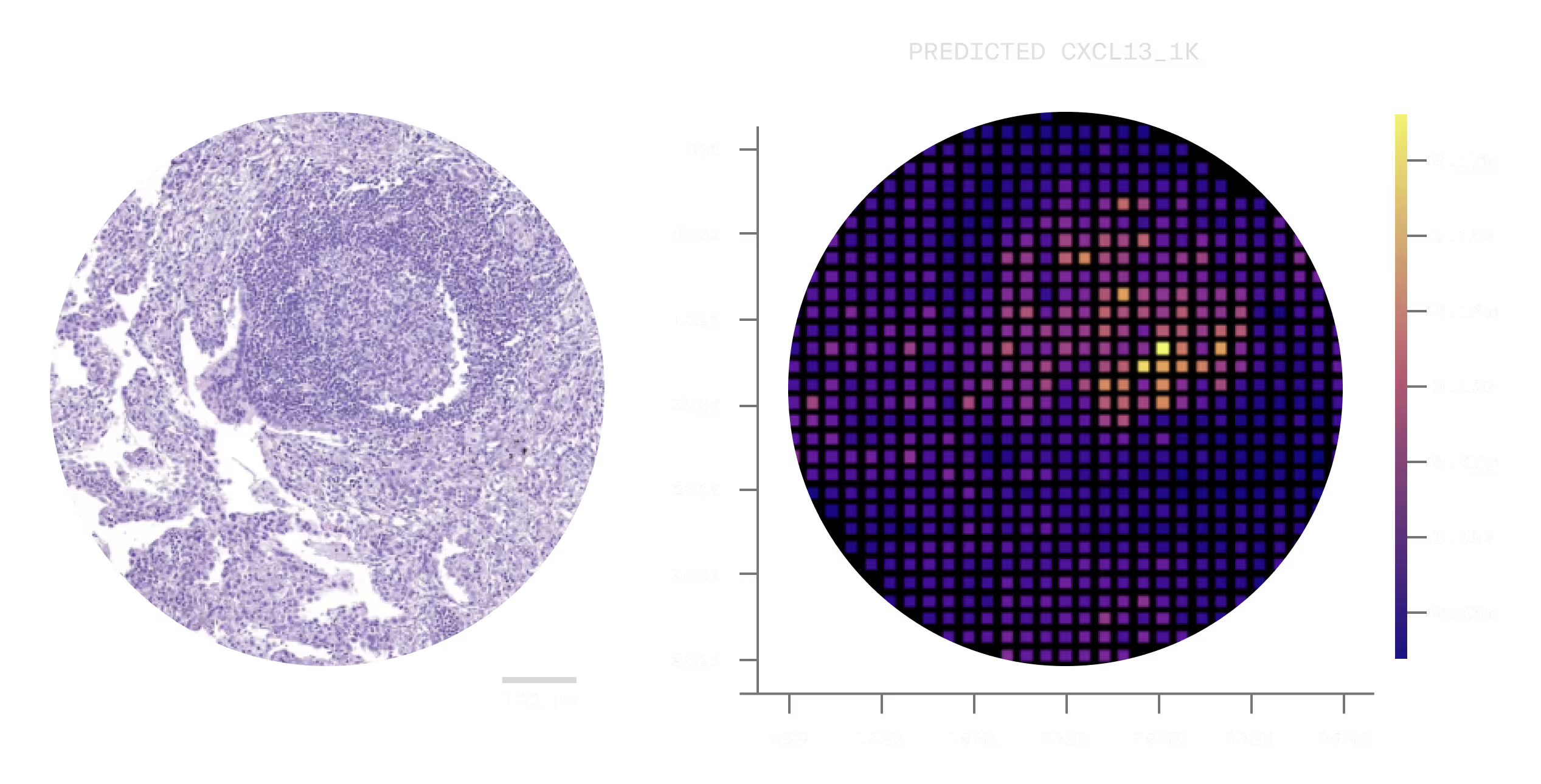

Spatial transcriptomics is the current gold standard for tumor characterization. But its cost and complexity have kept it confined to well funded research settings. In practice, most groups rely on H&E staining; cheap and universally available, but limited to morphology.

But spatial molecular signal is encoded in the H&E; it's just not visible to the human eye. Our model is capable of converting between these two modalities.

Using standard H&E scans, we can work with partners to convert them to spatial transcriptomics, offering high fidelity tumor characterization at a fraction of the cost.

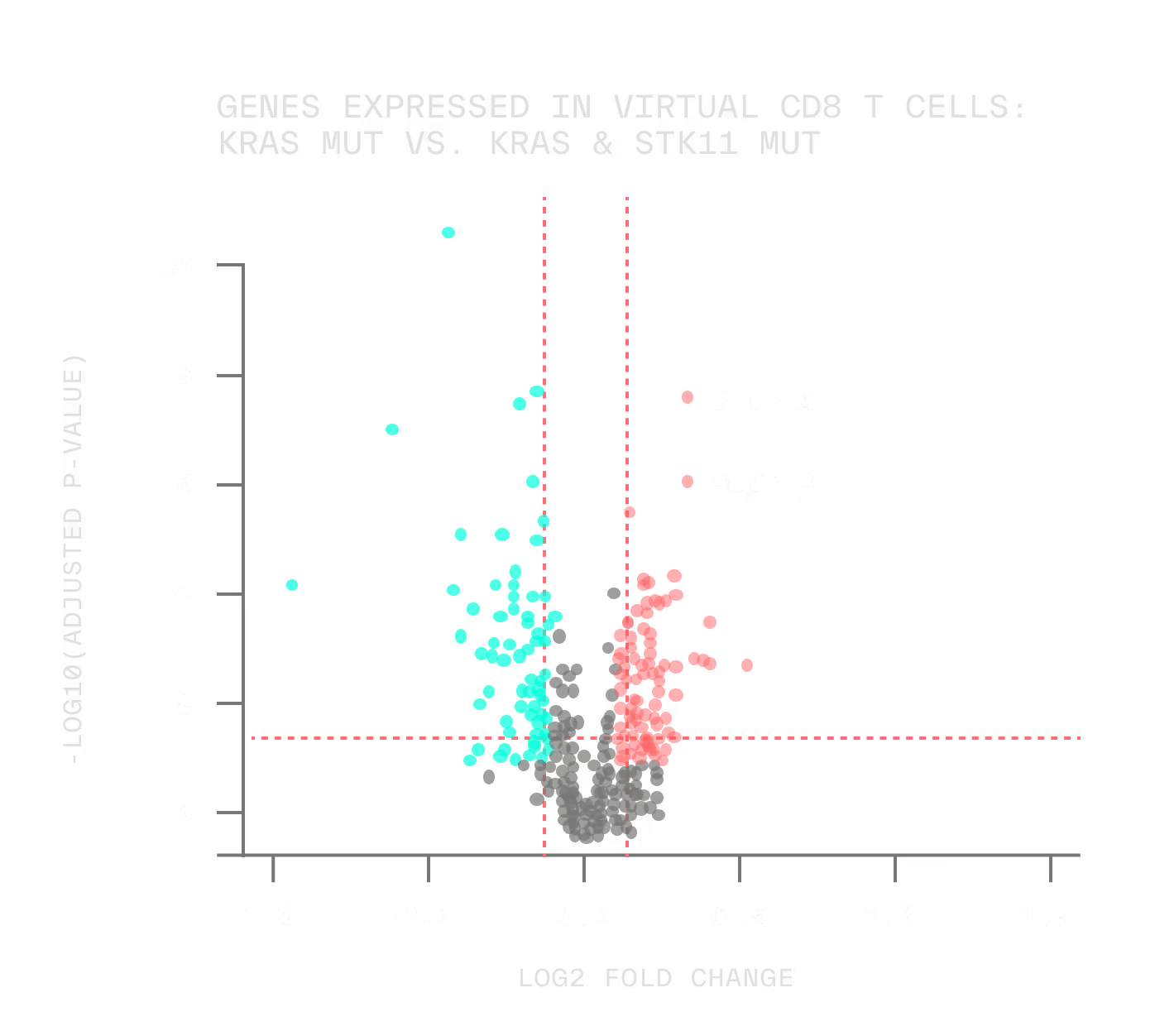

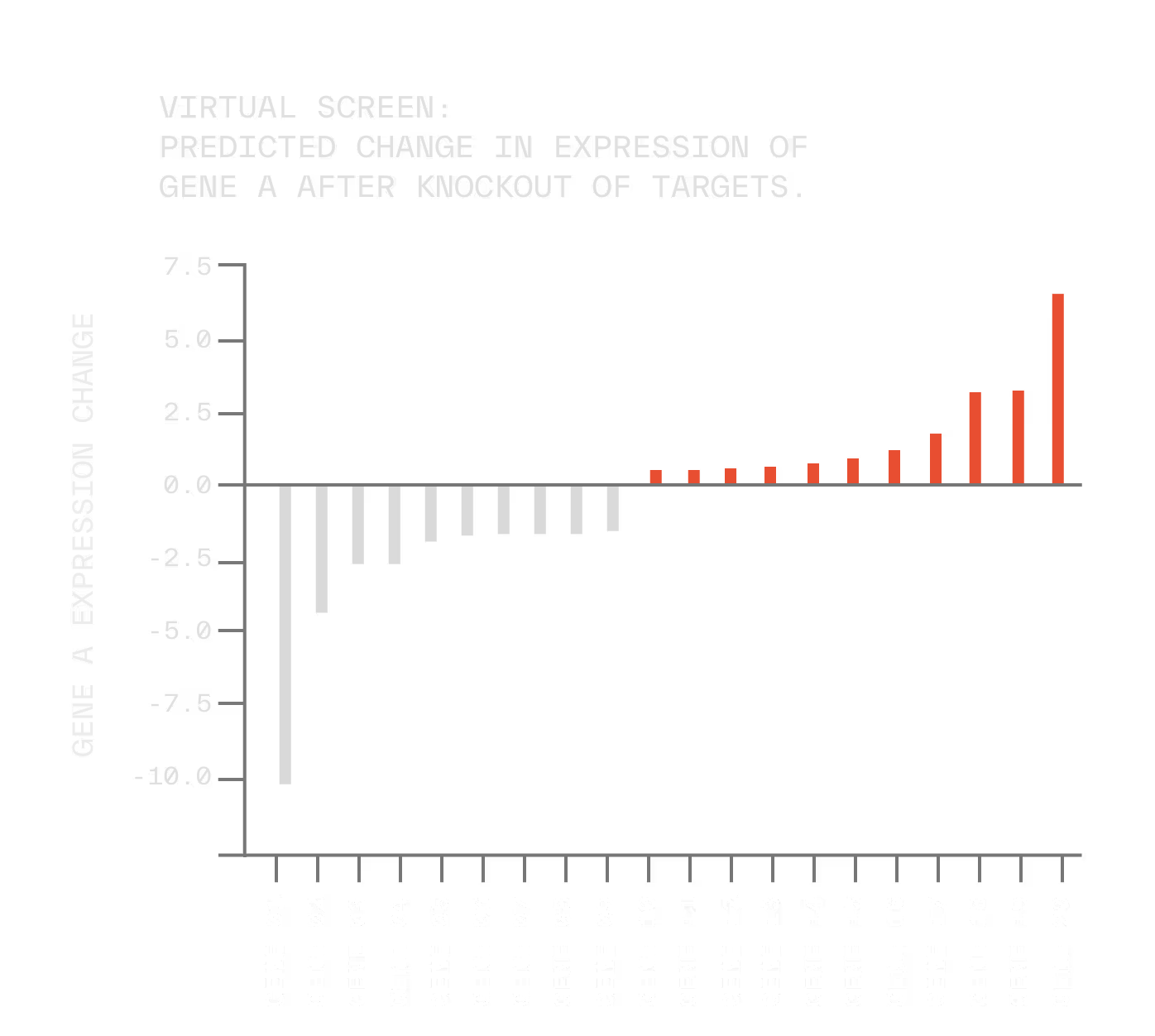

Our models have seen millions of different cells in a vast number of spatial niches, environments, and patients. As a result, they have learned how to simulate perturbations within a tumor, mimicking the mechanisms-of-action of existing drugs, combination regimens, or entirely hypothetical compounds.

This allows us to search the cancer therapeutic landscape in an unbiased way, discovering new cancer targets outright.

And when we find a perturbation that drives a tumor toward a less aggressive phenotype, we can even reverse engineer the biomarker signature that predicts which patients are most likely to respond.

All the above work can produce hundreds of therapeutic hypotheses, many of which must be validated further.

We can test these out at scale using a method called Perturb map. Using this process, we can introduce hundreds of tumor subpopulations in a mouse, each one with their own unique mutations suggested by our models, and spatially resolve their impact on the tumor microenvironment.

In singular runs of this process, we can gather hundreds of new ‘rules’ on what mutations not only do to the tumors, but also how they can change how therapeutics interact with them.

These rules are internally used for training models, validating clinical hypotheses, and understanding what slice of mouse cancer biology overlaps with human cancer biology.